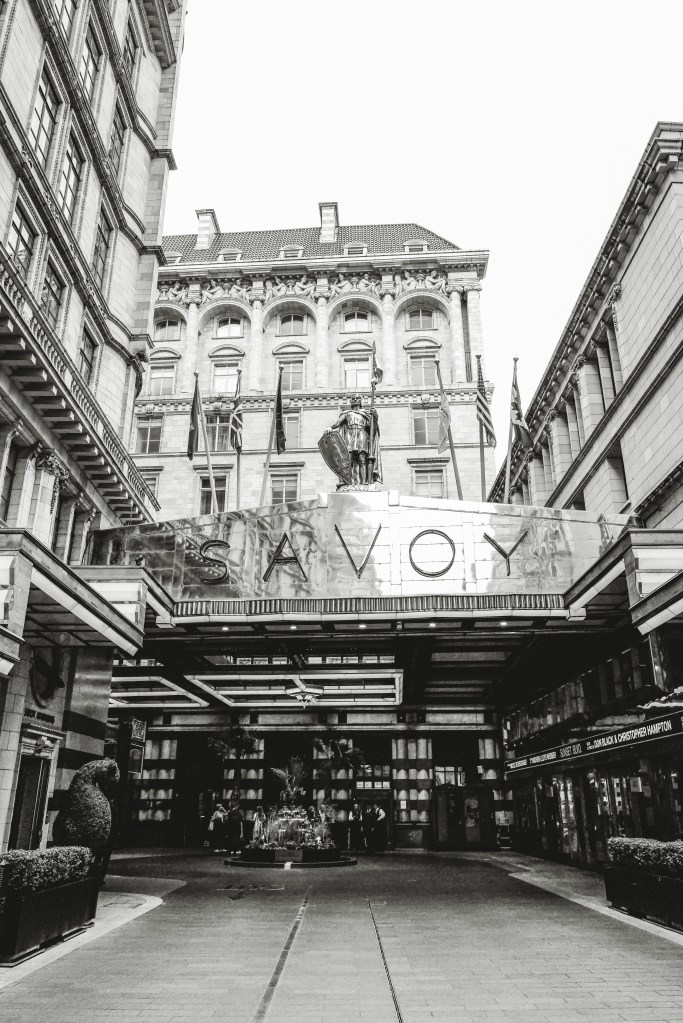

The Savoy

London

The Savoy is less a hotel than a chapter in the nation’s imagination. Check in here and you are not merely a guest; you are a footnote to decades of history, following in the steps of legends.

This was where Monet set up his easel and let the Thames shift beneath his brushstrokes. Where Noël Coward, Oscar Wilde, Frank Sinatra and Marilyn Monroe all slept and drank and dined. Where Dior staged his first London show in 1950, and Gucci used the setting to launch a modern collection seventy years later, and most evocatively for this author, my distant relative, Charlie Chaplin made a fifth-floor suite at The Savoy his home for three months after returning from four decades in America; table 85 in the Savoy Grill is still marked has his table.

Step into the lobby and you feel, almost at once, the tremor of all that past, as though you have wandered into the wings of a theatre mid-performance.

And yet, for all its gilt and grandeur, the Savoy’s trick is to make it feel like home. The doormen are the first act, immaculate in their livery, yet greeting you as warmly as an old neighbour. On every visit, doorman Rob remembers cleaning my bike, unprompted, from years before, a detail so improbable it continues to elicit a smile. That is the Savoy: detail, memory, service as instinct.

Our nights at The Savoy might not be in the numbers of the more famous Chaplin, but we are treated, I suspect, not hugely different. Our suites/rooms are always immaculate, our last visit affording us a junior suite, Edwardian in style, vast and serene, windows framing the Thames like an old photograph hand-tinted with soft colour. A dressing room large enough to absorb our theatrical luggage, a bathroom clad in marble and mirrored chrome. The bed consumed us whole; blackout shutters ensuring Covent Garden’s clamour faded into nothingness. My daughter’s sitting room became her own domain, complete with private bathroom. On one occasion she realised she had forgotten her mascara, and within minutes the staff, effortlessly, had arranged a replacement. It is the sort of incident that could be trivial anywhere else, but here it feels like the mark of a hotel that sees you whole, anticipates even your oversights.

Evenings begin, inevitably, with a Negroni in the American Bar. To sit beneath its Art Deco curves, amid the echoes of Gershwin and Sinatra, is to drink in history as much as the cocktail’s components. The bartenders are archivists as much as mixologists, each cocktail a story. And when the glass is set before you, perfectly weighted, you understand why this is one of the most famous bars in the world.

Over the years, Kaspar’s, the seafood bar has become The River Restaurant, a third Savoy gastronomic refuge from Gordon Ramsey, but it retained status as our favourite dining room, its marble counters shimmering beneath artful light, oysters and Champagne flowing in conspiratorial harmony. Service here, as elsewhere, was flawless without being stiff, staff gliding, almost balletic, between tables. On another evening we dined at the more relaxed setting of the Thames Foyer, under the glass dome, a pianist playing as if for you alone. Afternoon tea in that same space, scones as light as rumour, cakes sculpted with painterly precision, is a rite of passage. Even the Beaufort Bar, black and gold and theatrical, felt like the Savoy condensed into a single room: dark, glamorous, and faintly mischievous.

The hotel itself is a paradox. Vast, yet somehow intimate. Edwardian and Art Deco rooms cheek by jowl, as though a century has been carefully preserved rather than renovated. The corridors carry a hush, yet the restaurants and bars hum with life. Gordon Ramsay presides over many of the kitchens, Dior and Gucci haunt the recent past, but what endures is a sense of theatre: the knowledge that you are not the first, nor will you be the last, to fall under its spell.

Location, of course, is as central as London gets. Covent Garden, the Strand, the Thames Embankment, all within a sigh. Yet you feel, once inside, detached, as though the Savoy is floating a few inches above the city. There is a pool, quietly opulent; a gym; a spa. All superb, all eclipsed by the gravitational pull of the hotel itself. You may resolve to go out and see the sights, the theatres, the river, the West End, but more often than not you will linger, happily imprisoned by history.

The staff are the true custodians. A butler materialised to unpack us, though we declined with a smile; housekeeping left rooms so immaculate it seemed indecent to re-enter; waiters at breakfast anticipate our coffee order by the second day. On an early visit, a young waiter in Kasper’s took the time to explain the legend of Kasper the Cat [see below for details]…before bringing my then 5-year-old daughter a soft-toy Kasper of her very own to keep. And always the doormen, who somehow always remember us as if we are family returning, not occasional guests of a 268-room icon.

In the end, the Savoy is both legend and present tense. It is the laughter of Wilde, the brush of Monet, the music of Sinatra, the glamour of Dior, the cocktails of today. It is mascara fetched without fuss, bicycles remembered, Negronis mixed with the weight of a century behind them. It is Britain’s great hotel, still. And we will, inevitably, return.

“The Savoy is less a hotel than a chapter in the nation’s imagination.”

Footnote. The Legend of Kaspar the Cat.

The story begins in 1898 when Woolf Joel, a South African guest at the hotel, gave a dinner party to which only 13 were able to attend. He laughed off the old superstition that tragedy would fall upon the first guest to rise from such a gathering, and so the dinner continued. His friends’ fears were soon justified, when Woolf was fatally shot following his return to Johannesburg.

After this incident, the hotel always provided a Footman if a party had 13 guests to balance the number. However, as some of the dinner conversations were often of a confidential nature, Kaspar (a 3 foot high ‘wooden-eared’ black cat sculpture, made by Basil Ionides in the 1920s from a single piece of London Plane tree.) was conceived to become a convenient 14th guest, a tradition which remains to this day (Kaspar can be seen in a glass cabinet just of the main lobby area, when he is not dining).

When hosts find their private dinner parties attended by the unlucky number of 13 guests, they can request the pleasure of Kaspar’s company as the “14th guest.” The handsome cat is seated in a chair, draped with a dinner napkin, and is served each course as though he were one of the diners.